Docker Layer cachingFrom Docker docsLet's unpack the important bitsCan we make it faster?Conclusion References

It’s not too late to be early

Simply verify your ID, add a payment method, and buy crypto.

Achieving Reproducible and Cacheable builds with Gradle and Docker on Behind the Block

Discover how Blockchain.com tackled migrating to reproducible builds for JVM-based services within Docker while maintaining efficient CI workflows.

At Blockchain many of our backend services use the JVM stack - as such, they require a JRE runtime in the machine they run as well as a JDK to compile them. We package this runtime with our apps as a Docker image, and that is what we run in prod.

In this post we’ll explore how at Blockchain we navigated the difficulties of migrating to using reproducible builds for these services, while trying to still achieve quick builds in CI.

Context

We used to simply copy our compiled binaries into our images, which meant that developers might use JDKs to compile their builds different from CI’s, or run the apps on different JREs than those our images in prod use. This could result in hard-to-debug inconsistencies, like:

- A test failure in CI that is hard to reproduce locally in order to debug it.

- Two different docker builds originating from the same commit but resulting in different images, because they were built on different machines (each with its own JDK!).

- The solution to this problem, which we decided to adopt at Blockchain, is reproducible docker builds, thanks to the multi-stage build pattern.

There are plenty of good resources out there on reproducible docker builds, so I won't go into too much depth here.

For Gradle specifically, a reproducible docker build might look something like this:

# Build stage, example borrowed from https://mvysny.github.io/multi-stage-docker-build/

FROM openjdk:11 AS BUILD

# where . is where your sources are, including build.gradle(.kts)

COPY . /app # (1)

WORKDIR app

RUN ./gradlew --info --no-daemon build # (2)

WORKDIR /app/build/distributions

RUN unzip app.zip

# Run stage

FROM openjdk:11

COPY --from=BUILD /app/build/distributions/app /app/ # (3)

WORKDIR /app/bin

EXPOSE 8080

ENTRYPOINT ./app

This is the simplest possible multi-stage build: we copy over our sources (1), compile them (2), copy the resulting binary over to a slimmer image that doesn't contain the sources (3), and we're ready to run our app!

And this just might be good enough for your use-case.

Challenge

This solved our problem: make sure devs can reproduce what is going to run in prod.

But in our case, this brought new issues:

Long, boring build times

- Some of our older, bigger services take a long time (30 minutes!) to compile and test. This is usually fine, because Gradle is pretty smart when caching stuff. This partly thanks to its clever model of task graphs, which can result in a pretty fine-grained dependency tree where most stuff (be it recompiling, running tests, or coverage reports) does not happen again every time you change a line of code. But when you build end-to-end inside docker build, this caching goes out the window, resulting in building from scratch, every time, because Docker only caches up to (1) of the Dockerfile above.

No CI tooling

- Most CI providers (in our case, Github actions) will have some pretty nifty pipeline steps to improve dev experience or report on builds. Examples include summaries for test reports and coverage publishing. Again, if you build end-to-end during docker build, you cannot use these without having your Dockerfile speak to the internet - which is not desirable.

And so, we embark on the quest to achieve reproducible, but cacheable Gradle builds inside Docker multi-stage builds, that also allow us to inspect compiled code during CI.

Solution

Surprise! Due to the nature of how Gradle and Docker cache things, this is a futile quest. Allow me to explain:

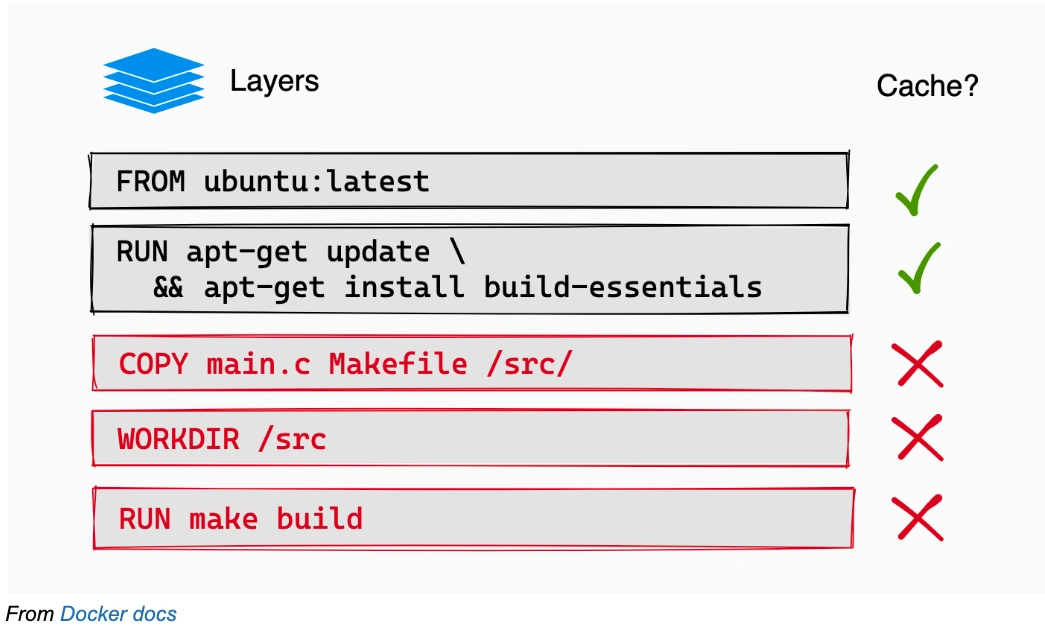

- Docker caches its steps in layers, like an onion, where each instruction in your Dockerfile is roughly one layer on top of the previous instruction.

- If the layers underneath are unchanged, there is no reason to not expect the next layer to have different results than last time - so we don't need to run it again.

- This makes sense for our multi-stage build example above: if I modify my sources, the COPY (1) command will change, and so I need to recompile the lot (2). If my sources are untouched, then no need to run gradle build again: we can reuse the result from the last time we did that.

Gradle, on the other hand, builds a tree of dependencies. If I have project B with subprojects B1 and B2 like:

app/

├─ B1/

│ ├─ build.gradle.kts

├─ B2/

│ ├─ build.gradle.kts

├─ build.gradle.kts

Gradle will not recompile B2 if I change the sources of B1, but will recompile the root project if I change either B1 or B2. Gradle does this at the task level, thus achieving pretty granular cache control (you can read more here).

This means that we can have two independent branches of the dependency tree, and we might only need to recompile one of them. This is unlike Maven, which uses sequential phases.

This fundamental difference in Docker's and Gradle's models means we cannot use Docker's caching for individual Gradle tasks, and so we will never achieve task caching in Docker, because in Docker we must run tasks sequentially.

This is sad indeed - you might be wondering why bother making a blog post at all? While we do not bring the perfect solution, there are a series of things we can do to mitigate this and still cache the bulk of the CI's work.

Docker Layer caching

The natural response to not being able to use Gradle's task caching is to use Docker's layer caching as much as we can!

From Docker docs

The way to do this is to break up the single big build step into several smaller ones, and make sure that the layers that change the most frequently (the hot layers) are the last ones, while the ones that change the least (the cold layers) are the first ones.

This will be extremely specific to your Gradle project, but we will take the example of a real Blockchain.com service that performs jOOQ and gRPC code generation, and is split into several gradle sub-projects, each with its test and assemble steps.

service-acme/

├── build.gradle.kts

├── settings.gradle.kts

├── gradle.properties

├── service/

│ ├── build.gradle.kts

│ └── src/

│ ├── main.kt

│ ├── kotlinSources.kt

│ └── ...

├── database/

│ ├── build.gradle.kts

│ └── src/

│ ├── migration_script.sql

│ └── ...

├── protos/

│ ├── build.gradle.kts

│ └── src/

│ ├── proto_definition.proto

│ └── ...

└── rocket/

├── build.gradle.kts

└── src/

├── kotlinSources.kt

└── ...

For this service, we can build a thoroughly layered Dockerfile like this:

FROM openjdk:11 as BUILDER

WORKDIR /build_app

# (1) copy root-level gradle config

COPY build.gradle.kts gradle.properties settings.gradle.kts gradlew ./

COPY gradle gradle/

# (1) copy the gradle files - this is not strictly necessary but it will help a lot when downloading dependencies,

# because most of them are specified in these files

COPY protos/build.gradle.kts protos/

COPY rocket/build.gradle.kts rocket/

COPY database/build.gradle.kts database/

COPY service/build.gradle.kts service/

# download dependencies layer (2)

RUN ./gradlew resolveDependencies --no-daemon --stacktrace

# protobuf codegen layers (3)

COPY protos protos # (3.1)

RUN ./gradlew protos:jar --no-daemon --stacktrace # (3.2)

# database codegen layer

COPY database database

RUN ./gradlew database:jar --no-daemon --stacktrace

# rocket compile layer

COPY rocket rocket

RUN ./gradlew rocket:jar --no-daemon --stacktrace

# service compile layer - only package the tar (4)

COPY service service

RUN ./gradlew service:distTar --no-daemon --stacktrace

# assuming the final tar's filename is `service.tar`: extract it so we can copy it out later

RUN tar -xvf service/build/distributions/service.tar -C service/build/distributions/

FROM openjdk:11 as SERVICE

WORKDIR /app

COPY --from=BUILDER /build_app/service/build/distributions/ /app

ENTRYPOINT ["/app/service/bin/service"]

Let's unpack the important bits

(1) Copies over the gradle build files, which specify the dependencies of each subproject. This allows us to run resolveDependencies (2), which will download all the dependency JARs. My assumption here is that what you change the least is the build config (and if it isn't then we can't cache it anyway!)

(3) Is the coldest layer in this specific example project - the proto subfolder which contains the .proto files which constitute this service's gRPC API. First we copy the sources over (3.1). Here we have to make sure that we do not copy files outside of this subproject's! Otherwise, this layer's cache will get invalidated every time we change them. Then we can run the jar task (3.2), which should call the codegen task (which calls protoc), and package it all up in a JAR, which can then be used in other subprojects, like rocket.

(4) Is the hottest layer in this example - the service subproject, which contains the main() function of the service, as well as the gRPC server implementation. My assumption is that if you make a PR to our example project, you are likely to be making it here! Just like we did for (3), first we copy the sources, and then compile them. This time we only package the tar - this is because we want to extract it in the next step, so we can copy the binary out of it and into the final image.

The idea here is that whenever we docker build this, only the layer that copies over the files we changed will need to be re-run (as well as all the later steps), and the rest will be cached. This assumes you set up Docker caching for your CI system.

Running tests outside of docker build, but still inside our image

The above Dockerfile is great for compiling our code, but you might have noticed I used the jar tasks - not build.!

This is because I specifically do not want to run our tests during docker build. But surely I will need to run them at some point, right?

This is where we get clever: while we cannot run them using our final image above (it does not even have the test sources) we can run them using the intermediate image we built in the BUILDER stage!

Here is an example for a Github action that does this (but you could implement it in any CI system):

compile-stage-service:

name: compile

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: Build service docker step

id: build

run: |

# (1) build the image up until BUILDER

docker build -f service/Dockerfile -t acme.built:${{ github.sha }} --target=BUILDER .

docker push acme.built:${{ github.sha }}

test:

needs: [ compile-stage-service ]

container:

# (2) built in previous step!

image: acme.built:${{ github.sha }}

steps:

- name: run tests # (3)

run: ./gradlew check

- name: publish test Report # (4)

uses: mikepenz/[email protected]

if: success() || failure() # always run even if the previous step fails

with:

report_paths: '**/build/test-results/test/TEST-*.xml'

publish-stage-service:

needs: [ compile-stage-service ] # you can also add `test` here, if you want to not push when tests fail

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: Build service docker step

id: build

run: |

# (5) build the image all the way now

docker build -f service/Dockerfile -t acme:${{ github.sha }} .

docker push acme:${{ github.sha }}

The idea here is that we build the image up until the BUILDER stage (1) - remember, this intermediary step still contains all the original sources.

Then we run our tests (3) in a container based on that image (2).

This means that we can now use tooling that would not be available to use if we were building inside the Dockerfile, like the junit-report-action (4).

You could add other steps here, like publishing coverage reports - the point is that you can now use all the reusable goodies that exist for your CI provider.! All without having to perform side effects during docker build.

Finally, we build the image all the way (5), and push it to our registry. This step should be pretty fast, because we already did most of the work in compile-stage-service!

If your CI runner caches Docker layers locally, this should be even faster because it should not download the BUILDER layers at all. Depending on what you are after, you can run this step in parallel with the testing, or only if the tests pass by adding needs: [ test ] to the step.

A possible setback to this approach: more gradle build layers means you start the Gradle daemon each time, which can be slow. Make sure you achieve the right tradeoff between splitting more layers so your caching is more effective, and starting the Gradle daemon little enough that it slows down your builds less than the caching speeds them up.

Can we make it faster?

Sure we can!

Sharing cached Docker layers between CI workers

The above only works well when cached layers get reused well. To make sure you achieve that, look into Docker caching storage shared by all your CI workers. This tries to make it so that if one worker builds a layer, a different one will likely not have to do it again.

Using the RUN --mount cache

Docker RUN --mount allows you to mount a volume during a build step. You can use this to cache the .gradle folder, which contains all the downloaded dependencies (as well as cached tasks' outputs, potentially!). This way, if you change a single dependency, you will not have to re-download the lot when you download the dependencies layer RUN ./gradlew resolveDependencies (1.1) of the Dockerfile above.

Conclusion

At Blockchain, we decided we were willing to compromise on faster builds for the sake of the guarantees that reproducible builds bring - but soon discovered we could have almost both! Hopefully you can use what we learned to achieve the same.

References

- Gradle docs: Build cache

- Gradle docs: Build lifecycle

- Docker docs: Multi-stage builds

- Docker docs: Mounts

- Docker docs: Cache management

- Docker docs: Caching backends

- Kostis Kapelonis - Docker antipatterns

Thanks to Florin, Jordan, Pavel and Lorna for reviewing this post.

This information is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended to substitute for obtaining accounting, tax or financial advice from a professional advisor. The purchase of crypto entails risk. The value of crypto can fluctuate and capital involved in a crypto transaction is subject to market volatility and loss. Digital currencies are not bank deposits, are not legal tender, and are not backed by the government. Blockchain.com’s products and services are not subject to any governmental or government-backed deposit protection schemes. Legislative and regulatory changes or actions in any jurisdiction in which Blockchain.com’s customers are located may adversely affect the use, transfer, exchange, and value of digital currencies.

Docker Layer cachingFrom Docker docsLet's unpack the important bitsCan we make it faster?Conclusion References

It’s not too late to be early

Simply verify your ID, add a payment method, and buy crypto.

Related News

Dec 5, 2024

Cheers to $100,000! Celebrating Bitcoin’ ...

Today marks a historic day for the cryptocurrency community. Bitcoin, the first ...

Nov 29, 2024

Black Friday Crypto Deals 2024

Black Friday & Cyber Monday Deals: Buy one .blockchain domain, get one free, and...

Jul 30, 2024

Celebrating 9 Years of Ethereum

Ethereum is marking its 9th anniversary! Learn about its journey from the initia...

It’s not too late to be early

Simply verify your ID, add a payment method, and buy crypto.